The Ledger’s Lock: How Double-Entry Bookkeeping Captured Our Economic Imagination

And How to Break Free

Introduction: The Grammar of Capital

Every system of power has its own language - a set of rules that make certain ideas normal and others invisible. For the world’s economy, that language is double-entry bookkeeping (DEB).

DEB is far more than a method for keeping track of money; it’s a way of thinking that shapes our laws, businesses, and even our moral beliefs.

This article explores how DEB became so powerful, why it’s nearly impossible to challenge, and how we can reclaim its language to make economics clearer and less intimidating for everyone.

Economics and its Accounting Lineage

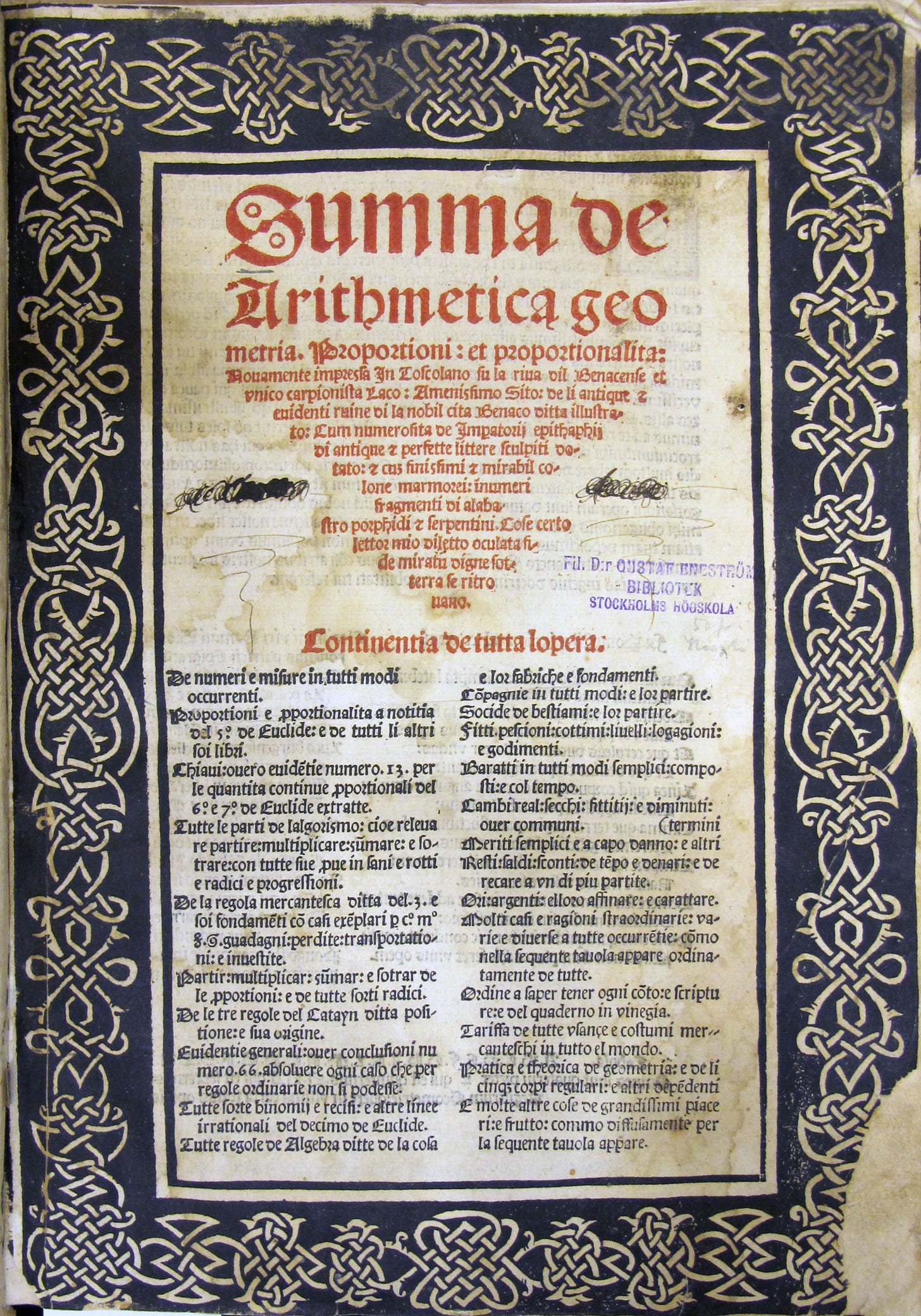

By Stockholms Universitetsbibliotek from Stockholm, Sweden - Titelbladet till “Summa de arithmetica ...”, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38104642

A Brief History: From Venetian Ledgers to Universal Logic

The formal system of DEB was first described in 1494 by Italian mathematician Luca Pacioli, but it was already being used in busy trading cities like Venice and Genoa. Its brilliance was simple: every financial transaction is recorded twice–once as a credit and once as a debit. This creates a permanent sense of balance. DEB wasn’t just a tool; it became a way of seeing the world.

The Birth of the “Firm”: DEB helped create the idea that a business is separate from its owner. This separation was crucial for the growth of big companies and, eventually, modern capitalism.

Governance: As countries centralized power, they used DEB to manage taxes, debts, and public spending. The idea of a “balanced budget” became a guiding principle.

Law: Corporate law, bankruptcy rules, and financial regulations all rely on DEB. Company balance sheets, checked for accuracy, are treated as legal documents.

Culture and Morality: DEB’s logic seeped into everyday language. Phrases like “in the red” or “balancing the books” now carry moral weight, suggesting that balance equals responsibility.

The Immovable Terminology: Why Change Is Not Just Difficult, But Perilous

Trying to replace terms like “deficit,” “debt,” or “liability” isn’t just an academic debate–it could cause chaos.

Risk of Collapse:

The global financial system is built on these terms. Changing them in one country could:

Break legal contracts worth trillions.

Confuse global markets for bonds, currencies, and derivatives.

Make financial laws meaningless.

Global Coordination Needed:

For change to work, every country would need to update accounting rules, laws, treaties, and software at the same time–a level of teamwork never seen before.

Institutional Resistance: Accountants, regulators, corporate lobbyists, and financial media all benefit from the current system. Changing the language threatens their authority and the status quo.

A Better Approach: Reframing, Not Replacing

Since we can’t change the terms, the solution is to change how people understand them. This means educating the public and shifting the narrative.

How the Current Terminology is Weaponised:

“Deficit”: Treated as reckless overspending, profligate and wasteful.

“National Debt”: Framed as a burden passed to future generations, like a maxed-out credit card.

“Government Liabilities”: Seen as risks owed to “creditors” (often portrayed as foreign).

The MMT Flip: Re-educating Through the Same Ledger

MMT (Modern Monetary Theory) doesn’t reject accounting–it completes the picture. It uses the same terms to explain how money really works.

Balance Sheet Basics: For every government “debt” (liability), there’s a matching asset for someone else. Example: “Your Treasury bond is an asset in your pension fund. The ‘national debt’ is just the flip side of our collective savings.”

Redefining “Deficit”: A government deficit isn’t a leak; it’s money flowing into the economy. The math is clear: Government Deficit = Private Sector Surplus. Saving money requires the government to spend more than it takes in.

Redefining “Sustainability”: Instead of focusing on debt-to-GDP ratios, ask: Is the deficit causing inflation by spending faster than we can produce goods and services? If not, the “debt” is sustainable. The real risk is inflation, not bankruptcy.

Methodologies for Narrative Change

Clarify Terms:

Use “Public Debt” instead of “National Debt” to emphasize shared ownership.

Pair “deficit” with “investment deficit” to highlight what’s missing, not what’s overspent.

Contrast “currency-user debt” (households, businesses) with “currency-issuer debt” (governments).

Use Relatable Analogies:

Scoreboard Analogy: “The national debt isn’t a credit card bill; it’s the score on a national scoreboard. It just shows how much of the government’s currency is being saved by everyone else.”

Shared Ledger: “The government’s red ink is the private sector’s black ink.”

Build Alliances:

Work with accountants, auditors, and lawyers to explain the national balance sheet.

Encourage economists and journalists to always mention “private sector assets” when discussing “debt.”

Focus on Purpose:

Ask: Why do we have a currency? Is it to chase accounting balances, or to mobilize resources for full employment, climate action, and public health? The ledger is a tool, not a master.

The “Branching” Metaphor

Original Branch: Technical jargon that’s precise but hard for most people to understand.

Rebranching: Using everyday language to explain the same ideas.

Semantic Preservation: Keeping the meaning while changing the words.

Practical Examples:

Medical: “myocardial infarction” → “heart attack”

Legal: “pursuant to” → “according to”

Tech: “optimize the user experience” → “make it easier to use”

Key Principles:

Stay accurate–don’t oversimplify.

Know your audience–adjust your language.

Context matters–sometimes precision is more important than accessibility.

This approach is valuable in fields like science, healthcare, and public policy, where experts need to communicate with non-specialists.

Conclusion: Mastering the Grammar, Changing the Story

We can’t break the “lock” of double-entry bookkeeping by force; we must pick it with its own tools. The goal isn’t to invent new terms but to reshape how people understand the existing ones–to strip away fear and reveal the truth they hide. This is a long-term project of cultural and economic literacy. By mastering the language of the ledger, we can write a new story where the economy works for people, not against them. The power of language is great, but it’s not unbeatable. It was made by people, and it can be remade by them.

👍🏻

You might like 'The End of Money and the Future of Civilization' by Thomas Greco

https://substack.com/@tomazg/posts